The Venice Biennale’s traditional site is the Giardini, public gardens created by Napoleon at the start of the 19th Century.

The first years of the exhibition saw more than 200,000 people attend the venues and over the decades since buildings have been erected to house country pavilions, showcasing artists and ideas from around the globe, catering to the crowds that come to see and experience the arts.

Upon entering the Showgrounds the first building is the Bookshop Pavilion. This beautiful building was designed by architects James Stirling, Michael Wilford & Thomas Muirhead, taking its place amongst the other architectural gems that populate the gardens. It is a joy to enter and walk through while admiring the books and publications that are a feature of the Biennale.

The country pavilions are spread across the venue. The Netherlands presents The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred showing the work of Congolese collective Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC). The group aims to redistribute and share the benefits that come from the international art market. In the space that smells of sculptures made of clay from Congo and recast in palm oil and cacao in the Netherlands, represent the extractive practices that have resulted in the loss of local power and ownership. The collective has reclaimed 200 hectares of former palm-oil plantation and is using that land to form more sustainable practices to benefit local people. A video plays as a livestream from a second venue, the Lusanga museum, once a palm oil factory for Unilever, linking to the Biennale in a sombre reflection on privilege and exploitation. The overall effect is strange and disjoining; a comment on the unbalanced nature of the world.

By contrast, The Canadian Pavilion uses glass beads, those items of antique trade. Kapwani Kiwanga’s Trinket makes use of hundreds of thousands of seed beads to blanket, coat and cover the pavilion, dividing the space with sculptures that reflect on the transoceanic trade that brought these tiny beads into contact with much of the world. Subtle and elegant, yet vibrant and alive, this is a beautiful rendition of a powerful idea.

Nearby, the Nordic Pavilion is marked by an enormous dragon’s head and tail, once part of a restaurant ship. Inside, Lap-See Lum’s work, Altarsea Opera, is a multidisciplinary collaborative piece with experimental composer Tze Yeung Ho from Norway and textile artist Kholod Hawash from Finland, on displacement and belonging. Using Cantonese mythical water creatures and taking the Red Boat Opera Company, a 19th Century travelling opera troupe that popularised Cantonese opera, as its premise, the bamboo-scaffolded artwork places audiovisual content amongst embroidered and painted robes. It is a fantastical spectacle.

In the main pavilion the works on display are largely visual art, although there are installations and sculpture scattered throughout. These artworks represent artists from across the globe through the portraits they painted.

There are many pieces to admire and some of them are:

Brazilian Candido Portinari‘s Cabeça de Mulato, 1934 shown here alongside South African Irma Stern’s Watussi Princess (1942).

Roberto Montenegro from Mexico painted Pescador de Mallorca (1915) while living in Europe when the First World War broke out.

Colombian Spanish painter, Alejandro Obregón‘s Máscaras reflects on political violence in Colombia.

Nigerian Ben Enwonwu‘s The Dancer (1962) is a rhythmic, dynamic portrait of a masquerade figure.

For more pieces in this section, see this link.

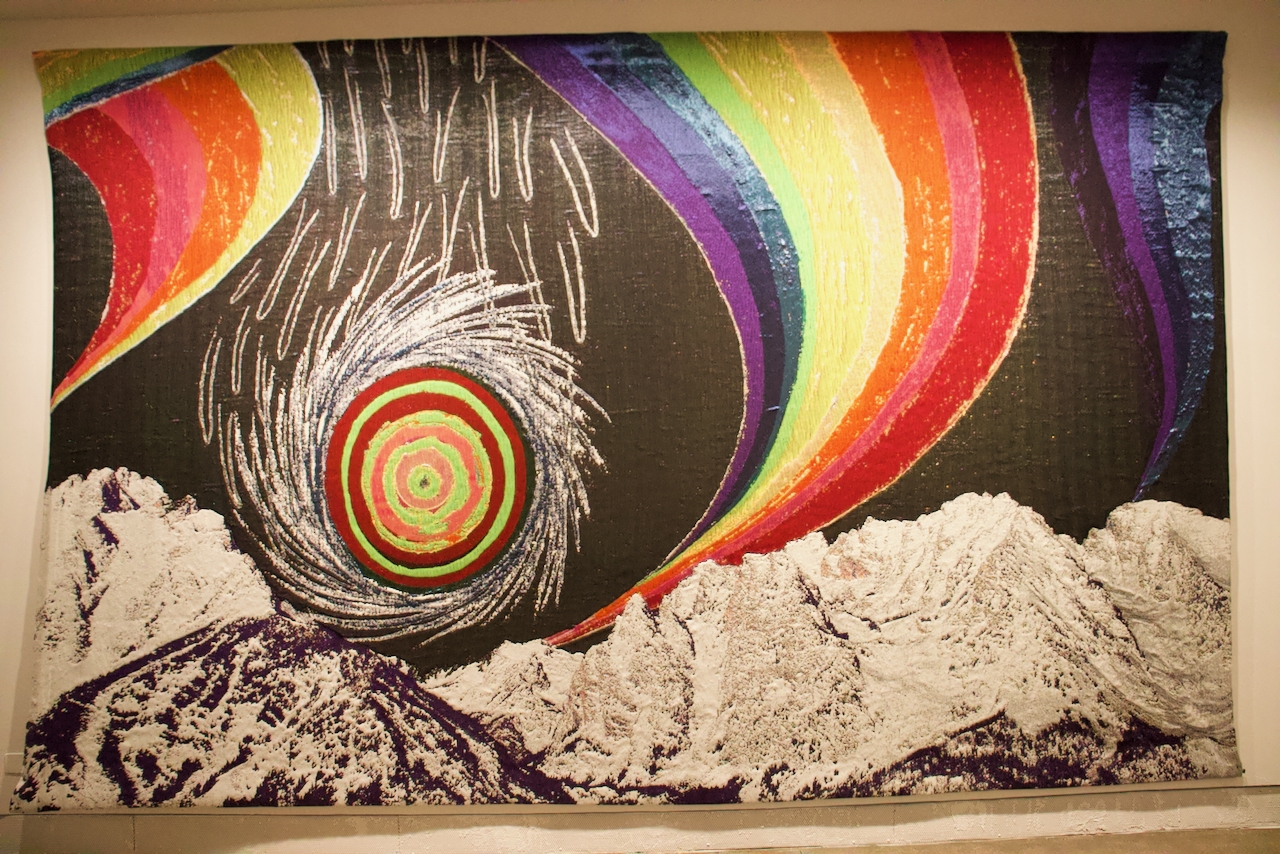

Liz Collins, the American fashion designer, has two pieces in the Biennale Giardini venue: Rainbow Mountains Moon and Rainbow Mountains Weather. These enormous Jacquard woven pieces flank a doorway; a reminder of the queer artists who are such a feature of this show.

Back in the Arsenale, Dana Awartani, a Palestinian Saudi-based artist has looked to the Arab world and India for her practice. In conversation with craftspeople in these and other countries Come let me heal your wounds, let me mend your broken bones (2024) is an installation that mourns the passing of historic and cultural Arab sites destroyed by war and acts of terror. Tearing and then darning silk lengths, the artist colours the fabrics in herb and spice-based dyes with medicinal properties before hanging them in space as markers.

Come let me heal your wounds, let me mend your broken bones (back) and A Espiral do Medo (2022) by Kiluanji Kia Henda from Angola. The latter is an installation created with protective railings from houses in Luanda, and accompanies a series of photographs of those railings in situ. The artist’s work looks at the disparities in the Global South, exemplified by these protective screens and rails.

Leave a Reply